Sourdough History Loaf4

The Slow Art of Sourdough: Returning to the Basics

Sourdough has been around for thousands of years, long before stand mixers, steam-injected ovens, or even standardized measurements. Our ancestors made bread with nothing more than flour, water, time, and a bit of intuition—no instant yeast, no temperature-controlled proofing boxes, no digital scales. And somehow, they made it work. As I embark on my fourth loaf out of 1,000, I find myself looking back at those early bakers, wondering how they developed a craft so precise and yet so deeply connected to the senses.

This time, I’m taking a step back. No shortcuts, no fancy techniques—just a slow, mindful approach to making bread.

A Look Back: The Origins of Sourdough

Long before packaged yeast was an option, people relied on wild fermentation. The oldest evidence of breadmaking dates back over 14,000 years, discovered in an ancient oven in Jordan. But it wasn’t until the Egyptians, around 4,000 years ago, that sourdough fermentation became common practice. By leaving a simple mixture of flour and water exposed to the air, they unknowingly harnessed wild yeast and bacteria to create naturally leavened bread.

For centuries, bakers operated by feel—measuring by handfuls instead of grams, relying on the seasons to dictate fermentation time, and kneading dough until it “felt right.” The pace of breadmaking was slow, patient, and deeply personal. It wasn’t a process to be rushed, nor could it be forced into a rigid structure. It was a dance between nature and the baker, a partnership that required trust.

With my fourth loaf, I want to tap into this ancient wisdom—to let time be my main tool and my senses my primary guide.

Mixing by Hand: A Different Kind of Connection

In my previous bakes, I’ve been tempted by efficiency. I used my dough hook attachment to speed through mixing, I followed precise hydration percentages, and I closely monitored fermentation times. But what if I let go of all that and just trusted my hands?

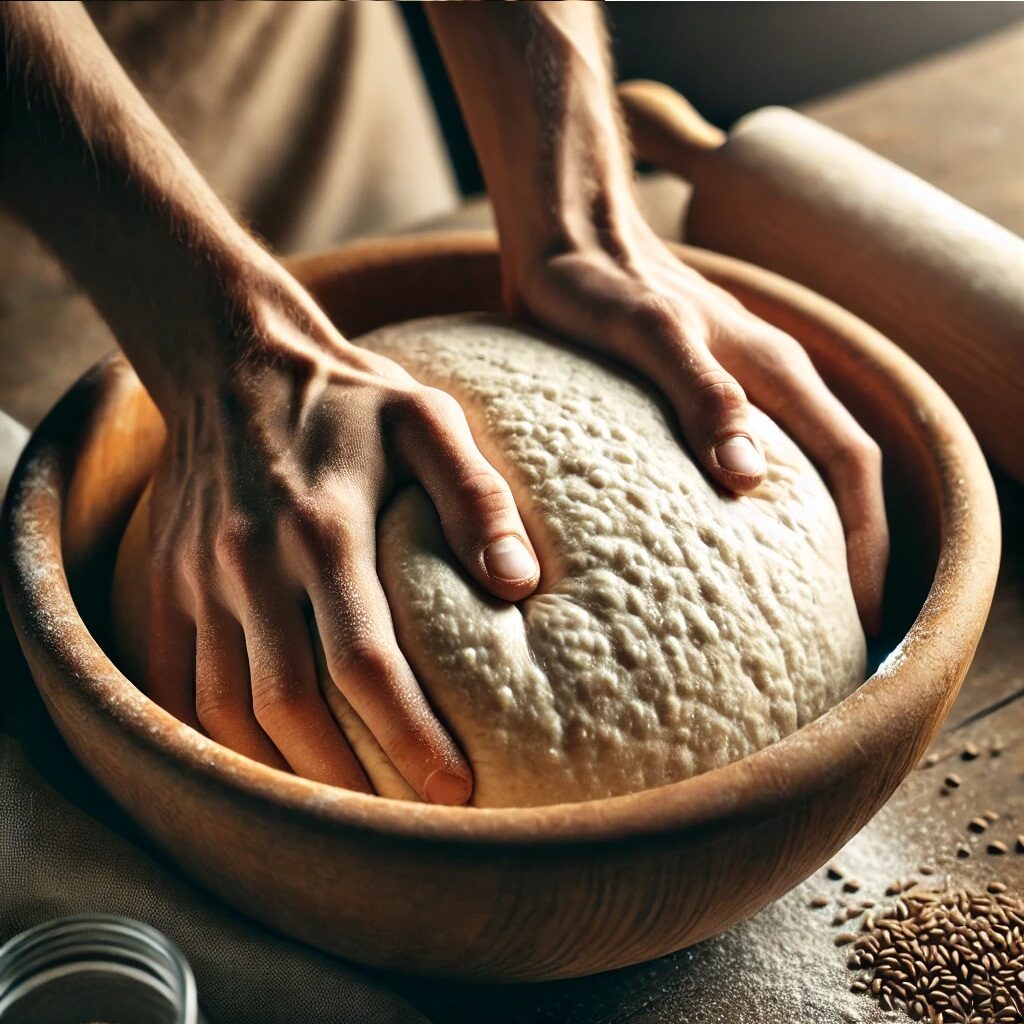

This time, I mixed everything manually. There’s something undeniably satisfying about feeling the transformation of flour and water into dough. At first, it’s sticky and shaggy, barely coming together. But as I stretch and fold, the gluten network begins to develop, and the dough takes on a smooth, elastic quality. It’s a reminder that baking isn’t just a mechanical process—it’s something tactile, something alive.

Slowing down also gave me time to observe subtle changes. The way the dough gradually strengthens with each fold, the way it relaxes between rests, the way it clings slightly less to my fingers as fermentation progresses. These are things I might have missed if I were relying on a machine.

Longer Fermentation, Deeper Flavor

One of the biggest lessons I’ve learned in my first three loaves is that good sourdough is as much about time as it is about ingredients. My first attempt was rushed, with a relatively short bulk fermentation, and while the bread was decent, it lacked depth. The second and third loaves improved as I experimented with cooler, longer ferments, but I still felt like I hadn’t given the dough enough time to develop.

For this loaf, I let the bulk fermentation go even longer, stretching it to nearly 12 hours at a cooler temperature. The result? A dough that smelled richer, with a noticeable tang even before baking. The extended time allowed the bacteria to produce more acetic acid, which gives sourdough its complex, slightly sharp flavor.

This longer process also had a historical tie-in. Traditional European bakeries, before the advent of commercial yeast, relied on long, slow fermentations because they had no other choice. The cooler bakery environments and natural fluctuations in temperature meant dough often sat for hours—or even overnight—before it was ready to shape. This method wasn’t a trend or a technique; it was simply the way bread had always been made. And it worked.

Baking and Gifting: A Cycle of Sharing

As I prepped my fourth loaf for baking, I noticed something different in the dough. It had a liveliness, a lightness, that I hadn’t quite captured before. The gluten structure was stronger, the fermentation bubbles more pronounced. The slower process had allowed the dough to fully develop, and I had a feeling this was going to be my best loaf yet.

When I finally pulled it from the oven, the crust was deep golden brown with a crisp, crackling surface. The scent was intoxicating—a mix of caramelized flour, tangy fermentation, and that unmistakable warmth that only fresh bread can bring.

And just like every other loaf in this journey, this one wasn’t just for me. I gifted it to a friend who had been asking about sourdough but never had the time to bake. There’s something deeply satisfying about handing someone a loaf you made from scratch, knowing that it carries a story, a process, and a bit of history within it. Bread was never meant to be hoarded—it was always meant to be shared.

As I move forward with the next bake, I’m carrying these lessons with me. Bread, at its core, is simple—flour, water, salt, time. But within that simplicity is an entire history, a deep well of tradition, and an endless opportunity to learn. And that’s what this journey is all about.

Write something…